Capturing the look and feel of a place in writing can be challenging. Fortunately, different kinds of genre fiction have some standard inspiration to pull from. For fantasy much of that inspiration can be drawn right from history. In this piece, we take a quick look into medieval towns, and town life in the medieval ages.

There’s never only one thing that characterizes fantasy, but as we’ve seen, most of these stories are cast in the backdrop of the European high medieval era, or some variation of it. While this time is rife with mythology about dragons, grand kingdoms, wizardry, and magic, one thing that sometimes get overlooked are the day to day details of what life in this era is like, including details on it’s various hubs of civilization, from villages to cities.

Today, I’d like to talk about the emergence of towns and cities, what medieval life looked like to someone living in that era, and pull some inspiration from it. Many of these things may be familiar to you, but theres rarely an opportunity where a writer, world-builder, historian, or other enthusiast doesn’t enjoy an immersive dive into this environment.

A few disclaimers: This article does not cover castle life or the ongoings of royal courts. Also, the sources for this overview come from Western European examples. Also, this article does not cover all aspects of medieval life, and is more focused on the emergence of towns and cities. Naturally, there’s so many fine details, so many nooks to see, so many cracks to fill in. However, let me just skim the surface and bring you into this environment. So, let’s dig in!

Life in the Middle Ages

In the high middle ages, much like today, your experience of the world was highly dependent on your role in society. You may be a peasant tilling the fields daily for a local lord, and treking to town once a few months, or once a year to offer goods to market. You may be a traveling merchant who is used to using the main roads, and witnessing town life in various corners of the countryside. You might be a lords or nobles personal messenger, a knight answering the call of war, clergyman, prioress, miller, blacksmith, scholarly clerk, noble… too many to count. In any case, your world is colored to the shade of your station.

Yet, regardless of shade, there are certain aspects that overlap into the full range of colors. One of the best pieces of literature that captures different walks of life is Canterbury Tales by Geoffery Chaucer. In this work, thirty individuals meet at the Tabard Inn, and decide to engage in a storytelling contest as they travel on their pilgrimage, each characters story depicting a unique view of life in this era stylized in various genres. What follows is a series of unique views of life within the era which take on various genres; romances, old legends, mystical fables, and allegorical tales. Together, readers witness a collage of the spiritual, the mundane, the fortunes and misfortunes of each soul embarking upon this journey.

Medieval Town Life: The Beginnings

In truth, medieval towns were few and far between. Most people within medieval Europe lived outside of the boundaries of towns as village peasants. However, the places where people congregated were often religious centers which benefited from geography which allowed stable construction and access to natural resources.

These budding towns often grew around central structure of some kind. The smallest could have a chapel at its center, a warehouse, a mill, or a pub or tavern which doubled as a town hall. Medium and large towns would typically spawn either from continued growth, or around a larger structure such as a castle, monastery, or similar. Some of the largest towns in England were cathedral cities (Canterbury, York, Bath, Lincoln, etc), which were often the site of pilgrimage.

Often, the streets following these structures were forced to adapt to the mound, hillside, river-bank, or landscape feature which the structure settled on. This sometimes meant meandering streets with irregular width, which required frequent maintained, lest they decay over time.

Trade and Guilds

The biggest attractor to these towns, however, was not religious pilgimage. It was the benefits of trading in the market. While they posed as a consistent center of trade, market fairs would pop up during vital growing seasons, pulling in villagers, traveling merchants, and others of seasonal visitors until the fair had ended.

Larger towns and cities would not only attract visitors from a broader region, but these larger settlements would draw in craftsmen from viable trade, and witness the establishment of guilds.

Guilds were the earliest form of corporation in medieval Europe, and the most prominent guilds emerged during the 12th century. Members often worked on their own account, and sold at the market. Those of the same occupation were gathered on the same street. (Tanners Street, Saddlers street). Each trade had its common coffer, its banner bore its respective patron saint, and each maintained its own regulations which specified conditions for admittance to the trade, who can vote in assembly, and provision meant to guard the honor and economic prominence of the guild.

Defences

Of course, trade could not survive the threat of catastrophe. Wars were frequent. Feuds between settlements and bandit raids could test populations living in a community. Even for towns, defenses were necessary.

Therefore, towns and cities were often surrounded by moat, or a wall. Depending on how prosperous the town, it could be shallow moats with wooden logs carved to a point, or trenches with clay brick or masoned stone. These wall could even have towers, either round or square. This gave an overlook for the town watch, and were intended for defense as well as decoration. One example of a sizable city was Nuremberg, known to have more than 80 towers in total.

Entering such a settlement would only be permitted through access gates, carefully watched. These were almost always closed at night to prevent nefarious types from entering under cover of darkness.

City-Planning

City planning was not much of a consideration until later in the era, and mainly for larger cities. The perimeter of walls meant that the area within was limited. Larger area meant more walls, which meant more overhead to keep the security of the town. Therefore, streets were kept narrow, premising only foot traffic and small carts. Streets were picturesque, but crowded, and full of obstacles preventing a comfortable movement across town.

It was later in the medieval era where cities decreed that key arteries in the city must be wide enough for a single knight to reach out in each direction with his lance. If an important avenue was not wide enough to do so, buildings would be torn down and rebuild to accommodate it. This is also why you are often to see houses and buildings with a narrower ground floor, with upper floors built wider, overhanging on large wooden beams so that they hung over the edge of streets.

However, towns and cities with deep history would have a combination of these two, older streets narrow and twisting, and large avenues wide with overhanging buildings. The most prominent of these streets or avenues were key arteries that stretched from the city gate to the central, as jagged or straight as the landscape would allow.

Many houses were built of wood, and the peaked roof was ornamented by a gable, or turret. These houses reflected the rank of those who lived in them. Those of greater wealth, honor, or nobility could look like a small fortress in the midst of the dense city buildings. Naturally, as professions in mining, stonecutting, and masonry became more prominent in the late middle ages into the 17th century, stone structures soon became the norm even amongst the poor. This was a vast improvement over wood as it allowed for a warmer and drier interior.

Government and History

While the scope of this article is medieval town life, its important to place it within the broader world. In the world that existed past the fall of the Western Roman Empire, after the chaos of failed successor states and barbarian raids, the Church managed to maintain literacy and religion. With the rule and passing of Charlemagne, what eventually emerged was a system of land owners and vassals known as feudalism. This military aristocracy maintained the class divisions between serfs/peasants, knights, and noble lords, albeit in a tenuous manner. Knights were mostly autonomous, and maintaining loyalty and conducting taxation effectively was a challenge.

The mid-and-late middle ages saw improvement to this system, as the ascension of strong kings and papal supremacy allowed stable systems of regulation, trade, and common law. Eventually, a region dominated by force and war would see the rule of law slowly prevail, though the rise and fall of Kings was frequent, with little hope of returning to the days of the Romans with a widespread, centralized order.

Far too much history exists in the middle ages to address in short words what this meant for town life, but the moving and shaking of Europe gave way to barbarian raids, changing dominions, Crusades, class oppression, city-states with mini-republics, knight orders, reprised trading across longer distances, the Reformation, resulting religious turmoil, multiple plagues and pandemics, emergent trades and technologies, absolutist monarchies, and eventually the precursors to our modern nation-states.

Law and Punishment

To understand law enforcement we need to understand that oversight was a limited affair in the olden days. Aside from the broad regulations of lords or kings, most towns were self-governing with local courts. They were guided by their own customs, with their own set of penalties and offenses, and their own methods of court procedure and enforcing local ordinances.

In the country-side and small towns, law enforcement was communal. Anglo-Saxon tradition, for example, grouped people into tithings of ten people who were responsible for one another. When a criminal committed wrong-doing, the community would call a posse to apprehend them by “hue and cry”.

Larger communities would have a community appointed officer who was tasked to keep the peace. They held the title of constable, beadle, or watchmen. However, sometimes this was not enough, such as with uncontrolled bandit problems, or with local lords who terrorized towns with private armies which became a growing threat. In time, centralized control would emerge as monarchs appointed their own Justices of the Peace.

Fair arbitration was not often the norm, and punishments were often harsh. Trials by ordeal, for instance, were the things of superstition and pseudo-science, and its examples were iconic; if one dunked in a cistern of cold water sank, they were innocent. If one grasped a red hot iron and walked a number of paces, based on how the wound healed or festered in three days determined their guilt. Many more examples exist of varying levels of primitive.

However, not long after did this era see a drastic evolution from ordeals in the 12th century, to the buddings of a criminal justice system with proper juries in the 13th century.

Wrapping up our Glimpse

This segways to perhaps the biggest takeaway of this piece. The era of the middle ages was so long, broad, and irregular that these pieces of culture saw a wide range of changes. Commoners, merchants, knights, and lords witnessed different qualities of life and customs between generations and centuries. In some ways, this shaped the lives of those living in these communities. In others, little much changed.

What I hoped to provide was a glimpse of this era through the words of not just historians, wars, or kings, but through the experiences of people. Even if we’re unable to truly understand the experience of someone in a place and time so long ago, these hints in history give us much to imagine. And that much, we have our own experiences to compare, and plenty hints work with.

Greetings, traveller! Are you seeking more content to fill your historical noggin and stimulate your imagination? Check out these articles below:

Or perhaps you’re looking for some fantasy or writing-related content. Check out these pieces below for more:

IMAGE CREDITS:

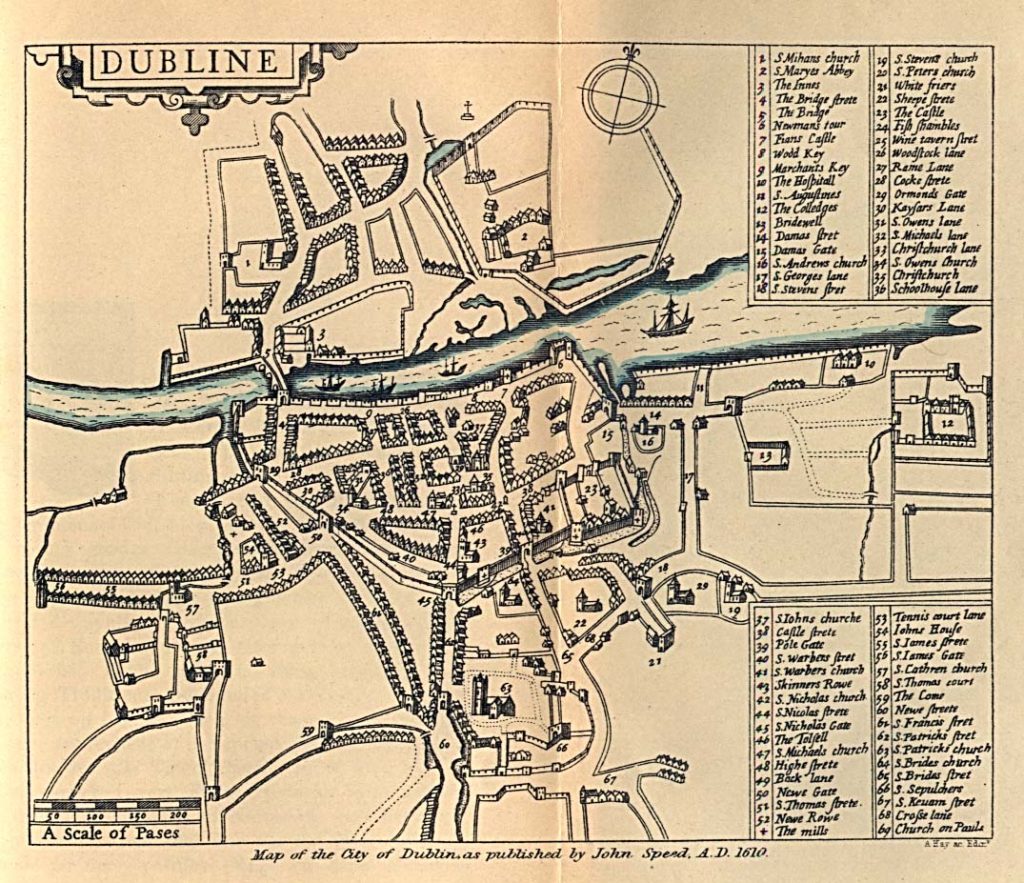

Featured photo obtained via Pexels, Free License, provided by user: Min An. … Photos obtained via Pixabay, Free License, provided by users: inkflo, MemoryCatcher, JACLOU-DL, and terimakasih0. … Illustrations are remastered public domain images from the British Library, and Maps are historic public domain illustrations, dated accordingly.

SOURCES:

https://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/medieval-england/medieval-towns/

https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Canterbury-Tales

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/candp/prevention/g02/default.htm

https://www.britannica.com/topic/government/The-Middle-Ages

https://today.law.harvard.edu/law-order-in-medieval-england/

(Unfortunately, this list is incomplete, missing a couple of video documentaries.)

- d100 City Encounters and Urban Sidequests - April 26, 2025

- Dirtbags! a Sci-Fi Shooter RPG: Gameplay Review! - March 23, 2025

- Nerds and Knights: a TTRPG “Nerd Nite” Presentation - February 28, 2025